That Very Black Melancholy

On Caribbean Reefs

I

In Walden, Henry David Thoreau writes, “There can be no very black melancholy for him who lives in the midst of Nature and has his senses still.” When I first came upon that quote as a teenager, I found it a particularly astute observation about the human condition. For all of my life, nature has been my release. When I am overcome with the weight of any particular emotion- sadness, stress, anguish- I have found no better elixir than the cool embrace of the Atlantic or watching the wind sweep through the meadows and forests near my home. My happiest memories, most formative moments, and greatest achievements have all been connected to my experiences with the natural world.

The conception that nature provided nothing but bliss was widely challenged during my month living on St. Croix in the United States Virgin Islands. To describe St. Croix as a paradise is not entirely incorrect, but it is a description that fails to encapsulate the reality of its environment and social scene. Picturesque beaches and fruiting trees abound, but much land has been cleared for agriculture and oil refineries. I don’t really want to stray into the crosshairs of local history and politics for the purposes of this narrative, so I will not elaborate on these environmental hazards but know they are real and poignant.

Where I found my emotions wavering and took issue with this quote that had seemed so true for so long was in the water. I spent countless hours in the calm, pristine waters of Butler Bay diving and snorkeling. Often alone, I was left with just my thoughts and the actions of the thousands of organisms that comprised the reef below. Coral reefs are without a doubt my favorite ecosystem to observe. Not even taking into account the color and physical form of the reef and its inhabitants, the reef presents the ecologically inclined mind with a venerable treasure trove of stimuli. When I am, say, in a forest, I may observe just one or two interactions between species at any given time due to the sheer scope of the forest ecosystem. A bird plucking a worm out of the ground, a plant in the midst of change as the seasons ebb and flow. While beautiful, the forces that connect these interactions play out here occur on macro scales and at a different pace. I’ve found this to be true in many other environments. For a diver on the reef, however, it is possible to see dozens of vital ecosystem processes unfold rapidly before your very eyes.

Diving from the surface of the water to the floor of Butler Bay’s shallow reefs, no deeper than 15 feet, brings a new world to life. Above the corals, bright juvenile fish zip to and fro in the blink of an eye, casting neon streaks against the backdrop of turquoise. Having caught a glimpse of perhaps the most annoying marine pest, Photographeris amateuris, they attempt to recede into the nooks and crannies of the reef. Oftentimes, they are chased out by the dusky damselfish, one of my favorite reef species. No larger than an index card, these creatures are fiercely territorial, often charging not only stray puffers and angelfish but occasionally ramming into my camera and mask when I got too close to the hole they’ve claimed as their own. Larger predatory fish (namely jacks and the occasional barracuda) circle the area, waiting for those younger and more inexperienced fish to slip up and expose themselves to their waiting jaws. Anemones and feather duster worms sway back and forth as they are jostled by the waves. Butterflyfish swim in schools of roughly two dozen, creating yellow clouds that dot the reef as they homogenize into one force moving with beautiful rhythm. Parrotfish, whose scales quite literally any color you can think of, proliferate.

The coral reefs of St. Croix offer beauty beyond those brightly colored inhabitants. An extended look at any patch of may expose a scorpionfish or octopus whose camouflage made them invisible at first glace. Massive brown pufferfish and timid pink squirrelfish can be found in large recesses. As reefs extend outward and provide more shaded shelter, lobster and shrimp lurk and eat the algae that grow on the surface of the reef. In deeper waters, massive barrel sponges provide domiciles for all manner of species. Massive stingrays, green sea turtles, and reef sharks often accompany me as I dive into these deeper waters. Go deeper still and shipwrecks provide an intricate artificial habitat for a whole host of residents. At night, the entire cast shifts and the reef becomes host to a whole host of new organisms that lie in waiting for the cover of darkness to feed safely.

And then there are the corals themselves.

II

I’ll start with my favorite - the elkhorn. A beautiful pale shade of orange fading to white at the tips of the extremities, these corals are vital reef builders, providing unique structure and habitat that supports large communities of creatures. Butler Bay was home to one particularly large and beautiful specimen that I visited daily, becoming well acquainted with the parrotfish that grazed beneath it and the wrasses and damselfishes that fought for territory in its upper branches. Within 50 feet of this coral were smaller elkhorns that appeared to be healthy and growing steadily, almost assuredly offspring of the large central specimen.

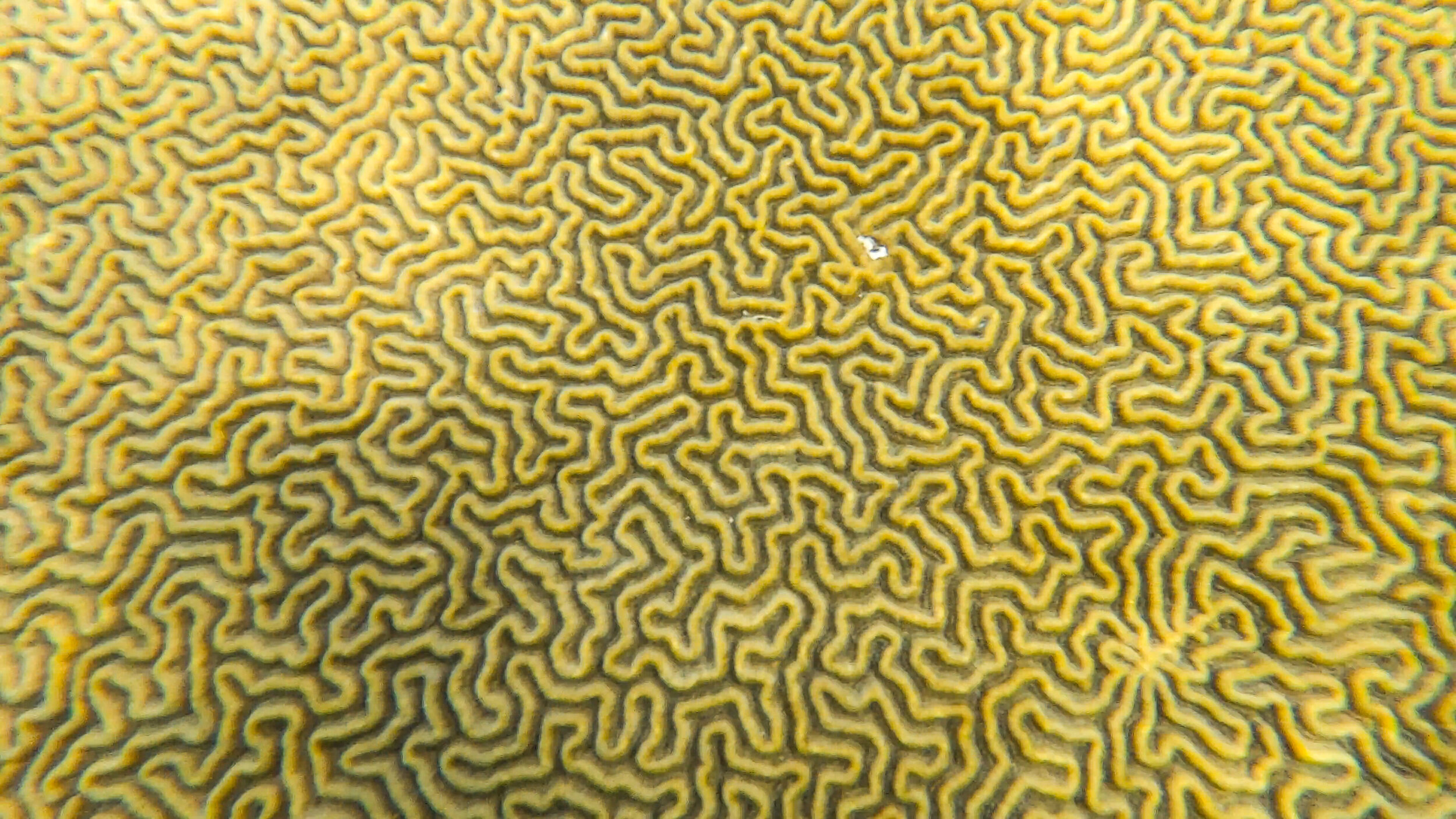

Elsewhere in the bay were massive boulders of brain coral. Yellow and labyrinthine, staring at these behemoths and following their patterns proved hypnotic. I spent many an afternoon simply examining every last groove on these creatures. The smallest organism on the reef found recess in these grooves, and those slightly larger hovered above it to feed. In rockier, protected areas, small pieces of staghorn coral attempted to colonize new territory. In the bay’s northern reaches are pillar corals that reach skyward and provide vital habitat for organisms seeking to escape large predators. Much like anemones, soft-bodied fan corals mimicked the motion of the waves. Bright purple and yellow, these organisms stand out from other soft-bodied corals on the reef, whose shapes mimicked trees and cacti and whose noodle-like appendages swayed in a fashion not unlike the inflatable men you may see in a used car lot.

You may think it wonderful to have witnessed such an ecosystem, and while it was truly a blessing, I was often overcome with profound sadness as I observed these ecosystems. Allow me to explain.

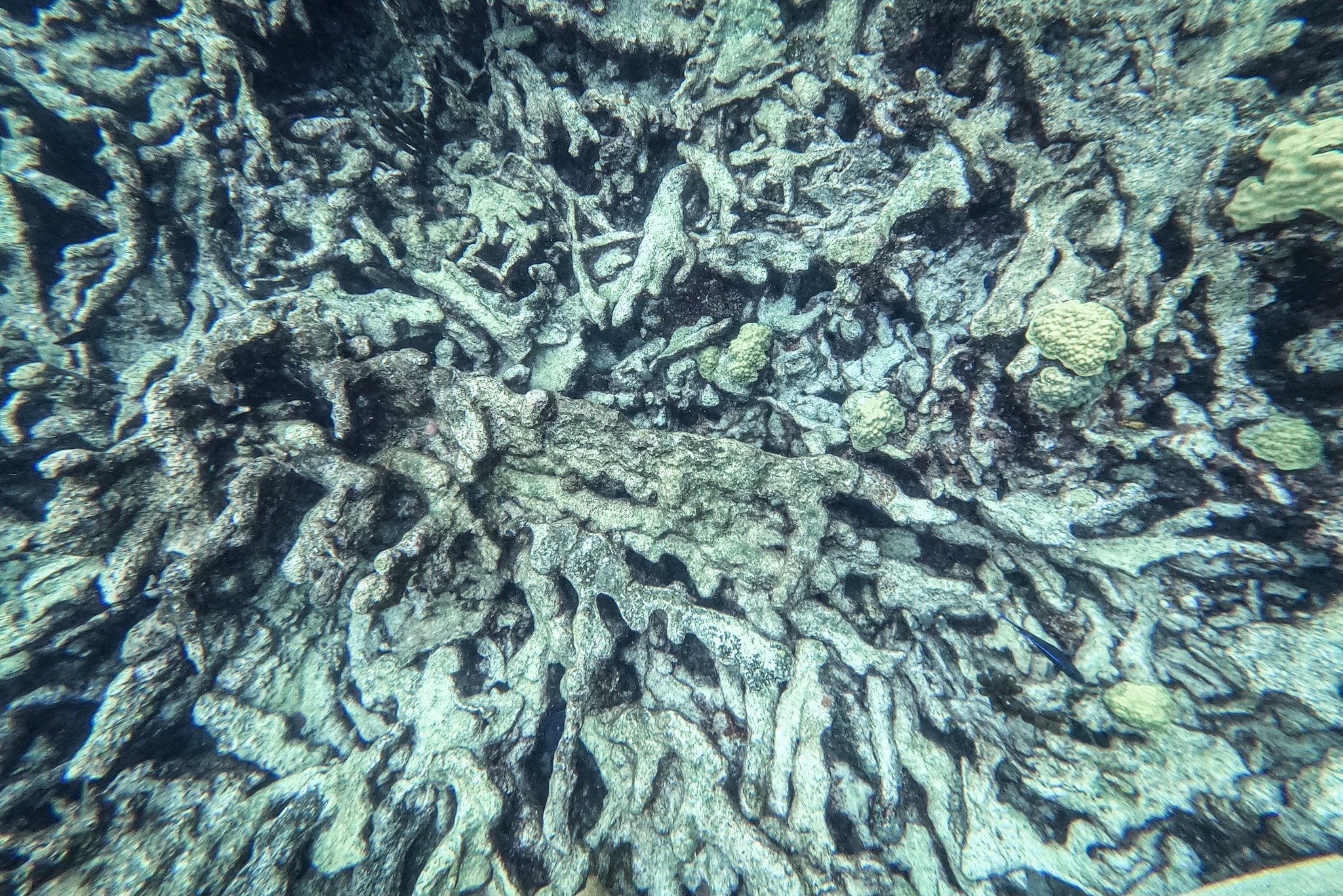

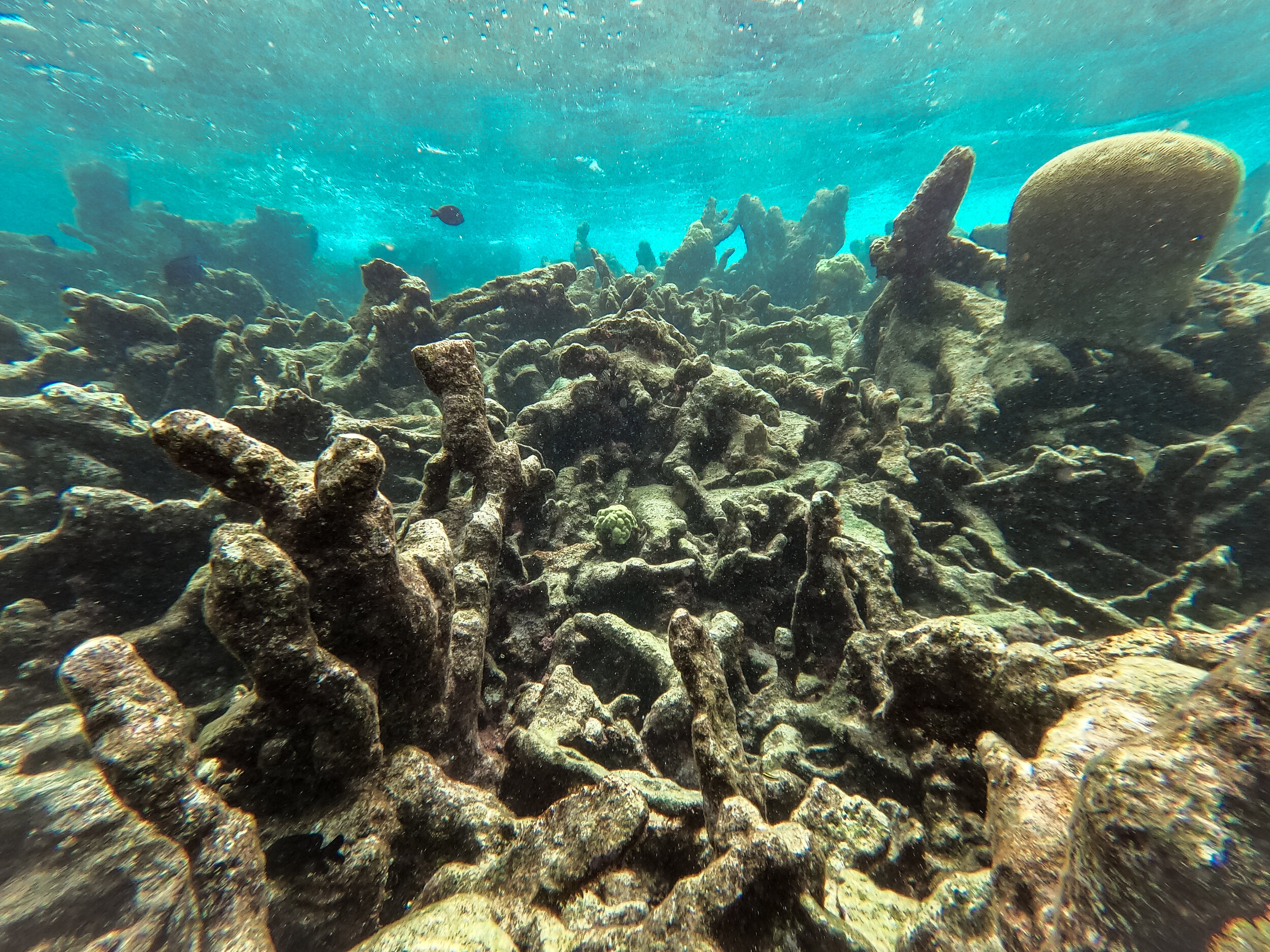

Elkhorn corals once dominated the Caribbean ecosystem. Massive structures branched out in a manner more than befitting their name. Now, however, their numbers pale in comparison. Elkhorns have suffered drastic population declines, with estimates claiming that from 1980 to 2006 their numbers receded by 97%. The rubble of former elkhorn fields now lay colorless, corroded, and rotting on the seafloor. Their bodies lie in disrepair and, apart from the interspersed parrotfish and schools of blue tang grazing on the algae that grow on their remains, they fail to support the species they once did. On one trip to Buck Island Reef National Monument, a site heralded for its protected elkhorn, I found it hard to stay in the water. I was physically ill and vehemently angry from the site of the death and decay that surrounded me. Dozens of branches of elkhorn laid rotting on the seafloor- with each one likely having died during my lifetime. To someone who understood that each one of these lifeless rocks on the ground was once a living organism, it was truly a disgusting sight.

In Butler Bay, far more common than the bustling, coral reefs are desolate stretches of rubble with no creatures in sight. Once vibrant reefs are reduced to monotone husks. Brain corals are blighted with black band disease and losing their distinctive color and pattern. The vibrant purples of the fans dulled as they fought off diseases of their own. As if a cruel metaphor, often one piece of coral would survive alone and be surrounded by nothing but the skeletons of their fallen comrades. Though I eagerly entered the water each day at Butler Bay, I often left unfulfilled and displeased. I began to feel annoyed with myself for taking pleasure in what little coral remained. Over and over, I found myself thinking just one thing: How the fuck did we let this happen?

I reflected on Thoreau’s assessment of our emotional attachment to nature, asking myself an unending stream of unanswerable questions. How could I be so miserable, so wanting, and so angered by the natural world? These ecosystems are some of the most captivating on our planet- what more could I want? Was this reaction appropriate? Should I have been only grateful to be in this position? Should I have been more upset with myself for coming here via airplane and dumping more CO2 into the air, thereby furthering ocean acidification and exacerbating climate change? Even if I dedicate my life to ecological conservation and restoration, will I do enough to outweigh my own negative contributions?

What right did I have to feel this way - I don’t even live there. I do not directly depend on coral reefs for food (though, like most everyone else on earth, I do by extension), nor do I rely on coral reefs to provide protection from storm surges or bring in tourism dollars. For generations, people and ecosystems from places I have never stepped foot in have suffered degradation because of myself and those before me. Is it a luxury to feel this way and not be placed at immediate risk by the collapse of coral reefs?

And, most importantly, what could I do to help rectify this?

III.

I’m back in New Jersey now. After a week or so visiting with friends and family, my heart again yearns to be out in the midst of nature. Suburbia offers just the smallest bits of this escape to keep me going. Summer rains collect on spider webs as their creators search for cover. Wrens & warblers volley calls from my left to my right, subjecting my ears to a sort of birdsong tennis match as I try to find the noisemakers from among their shadowy verdant dwellings. My slice of the Atlantic may not have coral reefs, but its creatures are nevertheless beautiful.

I still wrestle with these questions, but I believe I have arrived at an answer. Simply put, I cannot escape that very black melancholy which Thoreau speaks of because the coral reefs of the Caribbean in the 21st century are not natural. Though beautiful and truly joy-inducing at times, the skeletons of corals past and their accompanying somber feelings are a product of my species’ contribution to this ecosystem.

In his forward to The Nature of Nature: Why we Need the Wild, legendary naturalist Edward O. Wilson defines nature as, “everything in the universe beyond human control, from the sweet descent of her sunsets to the tantrums of her thunderstorms; from the explosive brilliance of her ecosystems to the black void of her empty space.” Unfortunately, perhaps the most explosive of these brilliant ecosystems have suffered unspeakable horrors at the hands of humans. Overfishing, dredging, pollution, and climate change have caused the collapse of the Caribbean reef ecosystem and threaten most every coral reef in the world. Whether we choose to acknowledge it or not, these ecosystems are now firmly within our control. Only by taking steps toward undoing this harm and furthering our coral conservation efforts can we return to nature to its natural state.

To limit our impact on nature offers promise far beyond the preservation of beautiful ecosystems. The preservation of coral reefs saves countless jobs in the ecotourism industry and generates revenue to keep people alive. The organisms that occupy coral reefs provide food for millions of people each day. Coral reefs allow for the sourcing of medicines that offer the promise of longer, more fulfilling lives. And yes, coral reefs are resplendently gorgeous. They fray out in magnificent fractals and contain colors seen nowhere else on earth. This natural beauty is critically important not only to tourists but to innumerable people and cultures around the world.

As for what I can do...there is little but this. In my small corner of the internet, I write this emotional plea for conservation and for people to take action into their own hands. To protect our ecosystems is to protect ourselves, our loved ones, and our future. It is a responsibility each of us must internalize and we must reflect in our lives, our votes, our purchases, and our recreating. My relative powerlessness is sobering thought- but it is nevertheless motivation to keep going. And if this little essay can make you think for just one moment more about a life at least partially devoted to conservation of our ecosystems, I’ll consider that a success.

If you enjoyed what you read, you’re welcome to send me a message.

Doing so lets me know I’m moving my work in the right direction and helps to inform future projects. Any and all feedback is very much appreciated!